Daniela Mateus de Vasconcelos, Doutoranda em Ciência Política, Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, Brasil.

Introdução

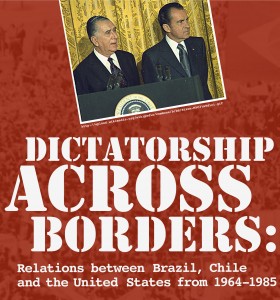

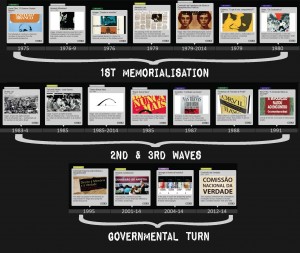

A presente tese de doutorado tem por objeto uma análise da singularidade do processo de enfrentamento do legado da ditadura militar no Brasil (1964-1985), em termos de violações dos direitos humanos perpetradas pelo aparato repressivo, com foco nos mecanismos de “Justiça de Transição” (transitional justice) adotados pelos governos civis pós-ditatoriais, sobretudo dos presidentes Fernando Henrique Cardoso (1994-2002) e Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva (2003-2010).

Problema de pesquisa: Por que não se produziu no Brasil, após o fim da ditadura militar, uma dinâmica de Justiça de Transição como ocorreu na Argentina e no Chile e, em menor medida, no Uruguai? Quais foram os obstáculos, ao longo do período democrático, à adoção dos mecanismos de Justiça de Transição no Brasil? Em suma, quais as razões da incorporação tardia e marginal dos valores e das práticas da Justiça de Transição pela democracia brasileira?

Hipótese central: a natureza da transição para a democracia ocorrida no Brasil, controlada desde o início pelos dirigentes militares, explica, em parte, o “tímido” padrão da Justiça de Transição. Esta variável não possui um caráter determinístico, pois consideramos que a singularidade da Justiça de Transição é influenciada por outros elementos relacionados a essa hipótese central, dentre os quais destacam-se a disputa de legitimidade democrática das narrativas construídas pelos atores políticos e sociais sobre o passado ditatorial recente (“os conflitos de memória”) e a fraca mobilização social pela bandeira da Justiça de Transição.

Objetivos e Metodologia

Objetivo geral: identificar e analisar as variáveis condicionantes dessa dinâmica de “acerto de contas” (settling accounts), nos seus eixos centrais da Verdade, Justiça, Reparação, Reforma institucional e Memória, que expliquem processo lento e tardio de adoção dos mecanismos de Justiça de Transição pelo Estado brasileiro, se comparado com aquele ocorrido nos países do Cone Sul.

Objetivos específicos: examinar os avanços, os retrocessos e os impasses da Justiça de Transição no Brasil nas suas vertentes fundamentais da Verdade, Justiça, Memória, Reparação e Reforma Institucional; analisar a ênfase dada nas políticas reparatórias em detrimento de outras medidas, tais como a instauração tardia de uma Comissão da Verdade, o indiciamento penal dos perpetradores e a reforma das instituições.

Metodologia: de base qualitativa, com foco na técnica de análise documental, a partir das seguintes fontes escritas: a legislação nacional; a legislação internacional (relatórios, estatutos e tratados internacionais de direitos humanos); jurisprudência internacional; relatórios oficiais de Comissões da Verdade; os informes não oficiais produzidos por organizações da sociedade civil (“Brasil: Nunca Mais”) os relatórios das Comissões de Reparação (Comissão de Anistia do Ministério da Justiça e Comissão Especial sobre Mortos e Desaparecidos Políticos).

Referencial teórico

A tese discute o repertório conceitual da Justiça de Transição, a formação e desenvolvimento do campo, a influência do Direito Internacional dos Direitos Humanos e das organizações internacionaisna sua difusão a partir dos anos 90. Ademais, recupera e discute os estudos pioneiros sobre transições para a democracia (a “transitologia”), ressaltando as potencialidades e limitações desse paradigma teórico para a análise das formas de enfrentamento do legado de violações de direitos humanos por meio dos mecanismos de Justiça de Transição.

Conclusões

A natureza da transição política condicionou o enfrentamento do legado de violações de direitos humanos pelos governos civis pós-ditatoriais. A mudança de regime político negociada, caracterizada pelo controle das elites autoritárias e seus grupos apoiadores, foi determinante para a ausência de iniciativas governamentais de Justiça de Transição na primeira década de democracia.

A Lei nº 6.683/79 ou “Lei da Anistia”, aprovada durante a vigência do regime ditatorial, garantiu uma transição sem grandes impasses no que diz respeito aos crimes contra os direitos humanos cometidos por agentes públicos civis e militares. A interpretação conservadora e restrita da Lei, ao anistiar os perpetradores das violações, favoreceu aqueles grupos que mais teriam que prestar contas frente a um processo de Justiça de Transição, sobretudo no campo da responsabilização criminal.

A transição brasileira abdicou de promover um “acerto de contas” com o passado recente por meio dos mecanismos da Justiça de Transição e relegitimou valores e práticas cristalizadas pela ditadura militar no sistema de segurança pública e no Poder Judiciário, assim como atores civis protagonistas no regime anterior, reinserindo-os ativamente na democracia.

A redemocratização brasileira conservou grande parte das prerrogativas das Forças Armadas (e também do Judiciário), “que continuaram a funcionar da mesma maneira como funcionavam sob o regime militar” (Pereira, 2010), com poucas mudanças do ponto de vista de um maior controle civil-democrático sobre as instituições militares e da subordinação das Forças Armadas aos poderes republicanos e constitucionais.

Apesar do crescimento do número de organizações de direitos humanos após o fim da ditadura, poucas foram aquelas que incorporaram a agenda da Justiça de Transição em sua plataforma de atuação. Segundo Abrão e Genro (2012: 71), “a luta por justiça de transição não constou da pauta desses novos movimentos sociais, ficando adstrita ao movimento dos familiares de mortos e desaparecidos políticos, sempre atuante e relevante, porém restrito a um pequeno número de famílias” e também às reivindicações por reparação do movimento dos trabalhadores demitidos ou impedidos de trabalhar durante o regime militar em função de suas atividades políticas.

Referências

• ABRÃO, Paulo; GENRO, Tarso. Os direitos da transição e a democracia no Brasil: estudos sobre Justiça de Transição e Teoria da Democracia. Belo Horizonte: Fórum, 2012.

• ARQUIDIOCESE DE SÃO PAULO. Brasil: nunca mais. Prefácio de Dom Paulo Evaristo Arns. Petrópolis: Vozes, 1985.

• PEREIRA, Anthony W. Ditadura e repressão: o autoritarismo e o estado de direito no Brasil, no Chile e na Argentina. São Paulo: Paz e Terra, 2010.

• SIKKINK, Kathryn. The justice cascade: how human rights prosecutions are changing world politics. Norton & Company: New York, London, 2011.

• TEITEL, Ruti. Transitional Justice. New York: Oxford University Press, 2000.

• TORELLY, Marcelo D. Justiça de Transição e Estado Constitucional de Direito. Perspectiva teórico-comparativa e análise do caso brasileiro. Belo Horizonte: Fórum, 2012.

@font-face { font-family: “Cambria Math”; }@font-face { font-family: “Calibri”; }p.MsoNormal, li.MsoNormal, div.MsoNormal { margin: 0cm 0cm 0.0001pt; font-size: 12pt; font-family: “Times New Roman”; }p.MsoFootnoteText, li.MsoFootnoteText, div.MsoFootnoteText { margin: 0cm 0cm 0.0001pt; font-size: 10pt; font-family: “Times New Roman”; }span.MsoFootnoteReference { vertical-align: super; }span.NotedebasdepageCar { font-family: “Times New Roman”; }.MsoChpDefault { font-size: 11pt; font-family: Calibri; }.MsoPapDefault { margin-bottom: 10pt; line-height: 115%; }div.WordSection1 { page: WordSection1; }

QUADRO 1 – Comparação dos resultados da Justiça Transicional: Argentina, Chile, Brasil e Uruguai

|

Questão

|

Brasil |

Chile

|

Argentina

|

Uruguai

|

| Anulação da autoanistia militar |

Não

|

Seletiva[1]

|

Sim

|

Não

|

| Civis isentos da justiça militar |

Não

|

Não

|

Sim

|

…….

|

| Expurgos no Judiciário |

Não

|

Não

|

Sim

|

……..

|

| Manutenção da Constituição promulgada pelo regime militar |

Não; nova Constituição promulgada em 1988 |

Sim; algumas reformas em 1990 |

Não, restabelecimento da Constituição de 1854, posteriormente substituída em 1994 |

…….

|

| Dirigentes do regime autoritário levados a julgamento |

Não

|

Não

|

Sim

|

Não

|

| Outros responsáveis levados a julgamento |

Não

|

Alguns

|

Sim

|

Alguns

|

| Comissões da Verdade oficiais |

Não

|

Sim

|

Sim

|

Sim

|

| Indenização das vítimas |

Sim[2]

|

Sim

|

Sim

|

Sim

|

| Expurgos na polícia e nas Forças Armadas |

Não

|

Não

|

Sim

|

….

|

Fonte: PEREIRA, 2011:58, com exceção dos dados do Uruguai, não incluído na pesquisa do autor.

Télécharger le poster de Daniela Mateus de Vasconcelos (PDF)

[1] “Alguns juízes interpretaram a anistia como se permitisse investigações (sem levar os acusados a julgamento) da violação dos direitos humanos. Além disso, alguns juízes determinaram que os desaparecimentos eram crimes que ainda corriam na justiça e, portanto, não eram abrangidos pela anistia” (Pereira, 2010: 238).

[2] “Indenizações foram pagas, em 1996-1998, a familiares de mortos e desaparecidos, no quarto governo civil após o fim do regime militar” (Pereira, 2010: 238).